I’ve just finished signing good luck cards and letters to our Year 13 leavers. I’ve always sent cards, although the luck has been angled towards exams rather than the further-off future, but a little luck never goes amiss. The letter, however, is a new, lock-down related departure: we would normally be able to meet to say our farewells and acknowledge the ending of school and the beginning of something new face to face, in an assembly, in a space where we would have been seeing each other, sometimes for the better part of seven years.

So, letters are on my mind. Even though new forms of written communication have developed, blogs no less, letters – confidential ones to individuals or open ones to all – do something which an article or a blog cannot do. A letter requires me to picture the person I want to read it and to try to imagine what they may feel and think as their eyes run over screen or page. Of course, I can invite others into my letter, the unattached reader, but a letter hangs on the personal connection it forges with its correspondent.

Although heads of private schools were not named in the letter which I mentioned in last week’s blog, the writers and signatories, recent black alumni of independent schools, were speaking to me (and heads of schools like Highgate) and, in my mind, I keep going back to it and its warning about the racist behaviour they faced as pupils in our schools: ‘It is precisely these sorts of attitudes and behaviours which, when left unchecked, can lead to tragedies.’ Of course, they had, they have, in mind the killing of George Floyd, but it’s the second half of that paragraph which hasn’t left me: ‘Racism is dangerous at every level.’

Highgate hasn’t been alone in reaching out to its alumni since the publication of that powerful letter: we asked all and any former pupils to be in touch with us, although we were most motivated to hear from those who might have wanted to be co-signatories to the letter had they had the opportunity or connection with those recent alumni who wrote: the candid, thoughtful, moving responses have shown the overwhelming (if unsurprising) urgency for a continuing process of listening and of dialogue. But there’s another letter (among many) which I’d like to write.

Dear younger OC,

I wrote recently to all OCs to ask you to be in touch with me about your experiences of racism at School, and I want to thank all of you who have reached out to the School: many of you have offered to carry on this dialogue and I am so grateful that you are willing to talk further. It’s clear how much listening we need to do.

Some of your experiences relate to a Highgate which is now distant, but these are nonetheless powerful for that. Some of you reflect on the wider reaction in this country – the protests in London, the questions over statues of white men who profited from the slave trade – and others on what the school did and didn’t do to prepare you for what you witnessed and are coming to terms with, the persistence of systemic racism in the thinking and behaviour of the establishment and of individuals, the gaps in your understanding at school of the historical and personal reality of black people growing up and living in London. However thoughtfully phrased or carefully contextualised, your feelings are of disquiet that your school, at best, could have failed to recognise the issues or, at worst, consciously ignored what we must have known already. You question the curriculum, in history, in English, in the humanities in general, in its omission of black history and culture, and in the opportunities missed in PSHE and the Knowledge Curriculum; you point to the learnt behaviour of minority black pupils to laugh off micro-aggressions; you ask why there were, are, so few black teachers and black pupils; you wonder where black pupils were meant to turn for support, and where white pupils were meant to learn about what you now know about your black friends’ reality.

You want action now but you are sceptical now that your school has muscled up its PR routines; your consciousness of a school’s reputation feeding its pupil recruitment makes you wary about actions which will come to the fore first and fast; you associate those in authority with defensiveness, prevarication and a tendency to live on borrowed time. You see evidence for this because you see little change since you left. Your school isn’t the only butt of your criticism but its responsibility for the generations which follow you worries you. You question how a school can promote values – even if some, many even, stand up to scrutiny – if it gets anti-racism and inclusion wrong. You want change, but you want it to be systemic and sustained.

You see the difficulty: while you want to hold your school’s leaders’ feet to the fire, you don’t want it to signal its virtues; you see that threat and anger in the country are creating fear and resentment. How are you to hold your school to account without sending the decision-makers running for cover?

If you’ve read this far, I hope that there is in fact enough patience to follow what we are doing and what we aim to do. You know that we have written to you, and we are following up your responses with offers to talk. We have embarked on a listening process with our BAME Year 12 pupils, led by OC Alexander Baleanu, supported by the Director of Wellbeing, Dr Emma Silver. On our Governing Body of eleven trustees, we have nominated two Lead Governors for Anti-Racism and Inclusion, Joan Deslandes OBE, Headteacher of Kingsford Community School in Newham, and Dr Saral Markanday, GP, who join a working party for inclusion and anti-racism, which will be steered by Salima Virji with a new remit for inclusion. Its initial remit will focus on the curriculum, on inclusion in admissions and staff recruitment, unconscious bias training for staff, particularly those making appointments internally and externally. It will be an inclusive group in its structure and membership, and pupils, whose councils are already tackling the issues of curriculum, the School’s history and its memorials, will be involved. We are planning a pupils’ society for African and Caribbean pupils, and asking whether there should be parallel societies for pupils of other ethnicities, and planning to establish a staff BAME group too. So, some of the ‘what’ is falling into place.

Of course, it’s going to be important to talk to white people about what we are doing and what they want to know, but we are taking what we have done and what we plan to do, to black colleagues, black alumni and black parents. You don’t need me to tell you that black experiences need to shape, inform, re-calibrate the reforming energy of policy-makers, especially where they have little or no first-hand, lived experience as a black pupil. So, in the short time since we have started these way overdue conversations I’ve been asked:

I know you’ve been diversifying your literature syllabus: can you make sure that my black narrative isn’t just about oppression, struggle and liberation?

How will you avoid making the revised history syllabuses you teach ones solely about the struggle between white and black? I think it will be important to correct the belief a lot of my friends had from their history studies that racial conflict is only an American issue.

When you confront racist behaviour, I want to know how you support those of us who call it out when everyone will know who we are, however confidentially you treat us.

I want to be listened to, but I don’t want to be singled out. I’d like to know how you can be sure I am heard?

You are talking about black people; I understand that. But does this mean other ethnicities won’t be part of the dialogue? Are our experiences less valid?

These questions – and they are only the very beginning – will, I believe, show us the way to make change that is systemic and sustained. Schools like mine, like yours, do need the space to enter into dialogue and to pick away at their preconceptions. We mustn’t become fearful of making mistakes or of being called out for what we haven’t yet done or haven’t yet committed to.

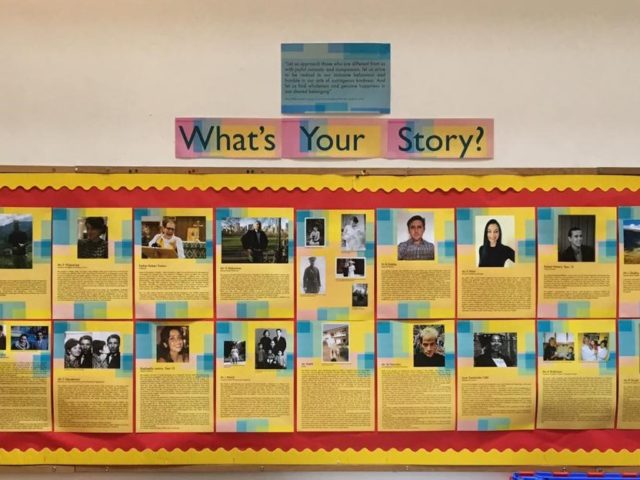

And I do think fear, in its potential to paralyse, is a great danger. And perhaps the antidote to this particularly virulent strain of fear is the realisation that what we want to do is intensely human and, while it may take time and will be unfamiliar, comes back to the essence of being young: inclusive learning, a diversified curriculum, this is necessary edu-speak for the joy of asking and discovering why am I here? Why are you here? What’s my story? What’s your story? This isn’t the intellectual equivalent of eating five-a-day for good moral and social health, but living out values in their entirety, critically, relentlessly, and chasing ‘not tolerating racism’ out of our timid behaviour, out of our safe lexicon, and replacing it with the vigorous, questioning, active anti-racism which you and your generation are exemplifying.

I hope you’ll see a commitment to change in what I’m describing, and I hope you’ll want to find out more. Keep in touch; come and see us and, please, keep talking.

With best wishes,

Adam