Taking a wander round Central Hall where Years 9 and 10 spend most of their day, to see how the teenage troops are faring, I was momentarily confused when I saw brown-paper-bagged offerings being dropped off class by class: I know that our kitchens are offering colleagues lunchtime take-aways to ease the squeeze of lessons which spread across the lunch hour, but I hadn’t heard about breakfast deliveries, and not in the hands of our librarians. But these turn out not to be egg and bacon butties, rather books which pupils now order and have brought to their form rooms. It was lovely to think that Covid-19 precautions have not put paid to library lending or to reading.

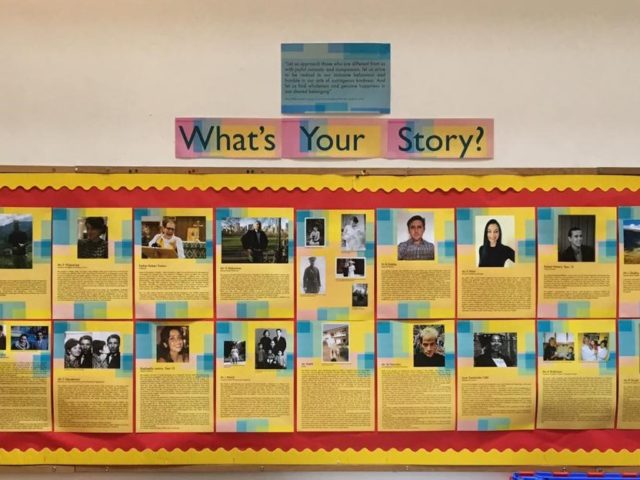

By now you will be familiar with the centrality to the School of its Central Hall: less so physically, now we reach out rather further along North Road than before, but in terms of what we do there. It’s a milling around space, a crossroads between Chapel and library, between common rooms and science labs, and a place for ideas: it’s where the Chaplain posts questions and invites contemplation; where the LGBTQ+ Group and the Feminist Society quiz, inform and reach out to us; where we are reminded where a trip to (or today, a takeaway from) the Library will take us; where student artists draw us into their imagined world; and it’s where we dwell on things which need to spill out and over the neatness of lessons and timetables. It’s where the display for our first Black History Month has succeeded our first display about inclusion, ‘What’s your story?’.

Our Head of History, Dr Ben Dabby, narrates a powerful assembly about Black History Month, and explains why the display which he and his colleagues have curated is titled: ‘Black History Month. A shared history. Beyond a month’. ‘The point of Black History Month,’ he makes clear in the balanced, gentle, optimistic tones we recognise so warmly, ‘is to encourage us to see how generation after generation of different communities have thrived on this island for centuries, meaning we can start to see that black history is part of being British whatever your heritage.’ He quotes from Professor David Olusoga’s brilliant book, ‘Black and British: a forgotten history’. No mere tributary into the broader narrative, no ‘bolt-on extra … deployed only occasionally in order to add – literally a splash of colour to favoured epochs of the national story […],’ Black British history ‘is an integral and essential aspect of mainstream British history’ which is too significant ‘to be marginalised, brushed under the carpet or corralled into some historical annexe.’ Let’s talk then about commemoration and history, about statues and controversies, about how we understand and compute imperial past and imperial legacy. About why our PM is probably wrong. It’s important, exciting stuff.

Opposite the Black History Month display Ms Niland chooses poems by writers of African Caribbean heritage and includes 2019 PEN Prize-winner Lemn Sissay’s Colour Blind, which finishes:

If you can see the white mist of the oasis

The red, white and blue that you defended

If you can see it all through the blackest pupil

The colours stretching the rainbow suspended

If you can see the breached blue dusk

And the caramel curls in swirls of tea

Why do you say you are colour blind when you see me?

From conversations I have had with friends, colleagues, pupils and parents, I know that I haven’t been alone in wondering about our blindness to so much.

Reading Olusoga’s work during lockdown, which has the searing, narrative pull and intensity of a novel, or being introduced to the writing of Bernardine Evaristo, so popular this summer that the publishers had to order emergency re-prints, or that of Pulitzer Prize-winning Colson Whitehead, now so well-known and admired that even sleepy Devon village bookshops could make recommendations of the next novel to read, it’s been a pleasure and a reassurance back at school to find ourselves in the guiding hands of colleagues who look forward, who are optimistic, who see opportunity for transformative change. To be with pupils whose energy and conviction breed confidence about what is possible. After all, what are schools for but for learning? For making progress without worrying about mistakes we may make along the way.

Throughout these last months since George Floyd’s murder, I’ve been very lucky to have partners in dialogue: Black colleagues and alumni who have been happy to talk candidly about their experiences as Highgate pupils and co-workers as we try to turn our good intentions into actions that will make a difference, to turn deeper understanding and empathy into long-lasting change. We were exploring teacher recruitment when someone, himself a Black alumnus of an independent school, and an expert in diverse recruitment, sensing the concern about ‘why only now’ said: ‘Skip the preamble and skip the look backwards – we are looking forward and being progressive. Nothing for people to feel bad about – we just feel a need to make our teaching staff be more representative of our area and of the pupils we wish to teach.’

Let us not dwell, then, on blindness of the past, but rejoice in reading and learning about it and rediscovering and sharing this lost, common history. Let’s make sure those paper-bagged deliveries, bearing Olusoga or Evaristo, Whitehead or Sissay from the Library, continue. There are past blindnesses we can forgive; the present needs wakeful watchfulness.